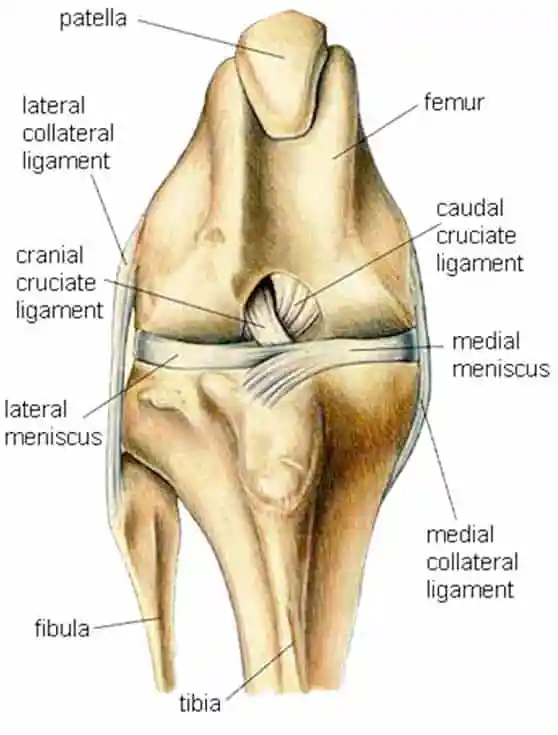

Let’s look at the anatomy of a canine knee joint. The way the stifle (or knee) in a dog is situated, there is a major ligament located on the anterior of the knee that plays the role of providing stability to the knee joint. It achieves this stability by attaching to the anterior of the joint, stabilizing the femur on the tibia. In dogs this ligament is known as the cranial (also sometimes referred to as canine) cruciate ligament, or CCL. There is also a ligament located on the posterior of the knee known as the caudal cruciate ligament which provides secondary support to the joint.

The human knee also has ligaments with anterior and posterior attachments that provide stability. In humans they are named for these attachment points and known as the Anterior Cruciate Ligament, or ACL, and the Posterior Cruciate Ligament, or PCL. As far as dogs are concerned, the specific acronym used makes very little difference.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injuries are one of the most common orthopedic injuries veterinarians see in dogs. The ligament is also known as the Cranial Cruciate Ligament (CCL) in animals. It connects the bone above the knee (the femur) with the bone below the knee (the tibia). Essentially, the ACL stabilizes the knee (or stifle) joint. It does not matter the size, breed, sex or age of the dog, all dogs can get an ACL injury. That said, studies have shows certain breeds are more prone to ACL injuries. These include: Labrador Retrievers, Poodles, Golden Retrievers, Bichon Frises, German Shepherd Dogs, and Rottweilers.

An ACL injury is extremely painful and affected dogs experience pain while simply walking. A tear or rupture leads to joint swelling, pain and instability in the knee joint. If left untreated it will cause lameness in the affected rear leg and, ultimately, chronic irreversible degenerative joint changes. Damage to the ACL is a major cause of progressive osteoarthritis in the knee joint of dogs.

Darryl L. Millis, MS, DVM, DACVS, DACVSMR, CCRP

Professor of Orthopedic Surgery & Director of Surgical Service

Robin Downing, DVM, MS, DAAPM, DACVSMR, CVPP, CCRP

Diplomate of the American Academy of Pain Management, is a a founder and past-president of the International Veterinary Academy of Pain Management.

Janet B. Van Dyke, DVM

Diplomate American College of Veterinary Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation, CCRT, CEO

Ludovica Dragone, DVM, CCRP

Vice President of VEPRA, Veterinary European of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Association.

Andrea L. Henderson, DVM, CCRT, CCRP

Resident, Canine Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation

Steven M.Fox, MS, DVM, MBA, PhD

President Securos. Inc

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injuries can be caused by many factors, although the exact reasons as to why it is so common in dogs is not completely understood. Continual biomechanical wear and tear eventually causes the Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) to break down until it reaches a point that the ligament tears completely. Simple activities such as walking, running and jumping, all cause wear and tear. Obesity, traumatic injuries or strenuous or repetitive activities can also cause the Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) to deteriorate.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injuries in dogs do not always occur during athletic activities. Some dogs will be making a simple movement like jumping off a couch or going down a stair when their Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) will tear or rupture.

Most acute (sudden) Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injuries in dogs occur during strenuous or exuberant activities, such as playing, chasing, roughhousing, running, hunting, jumping or engaging in other “doggie” fun. Sometimes a dog will simply stumble and when they get up they will have ruptured their Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) . Other times Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injuries will develop slowly over time. This can be caused by genetic abnormalities that cause poor muscle tone or poor neuromuscular coordination. Obesity also contributes to chronic ligament damage because of the extra weight placed on the joints.

Often symptoms of ACL injuries are gradual and a dog will slowly become more lame as the ligament becomes more damaged. Other times, when there is a rupture or tear, there is no advanced warning signs. Nearly all dogs with tearing or damage to their cruciate ligament will have swelling that is felt on the front part of their knee.

Symptoms may include:

Platelet rich plasma therapy (PRP) has been used with success to treat arthritis in joints, muscle, tendon and ligament damage. In this process, the blood is drawn from the patient and then centrifuged to concentrate the platelets as well as remove the majority of white and red blood cells. Then, the plasma is injected back into the patient at the site of the injury. Its injection may be peppered along the site of the injury to maximize its beneficial effects.

Stem cells have also been researched in conjunction with new tissue generation. Just as in PRP therapy, stem cells bring growth factors to the site of the injury. However, within 24 hours of injection as many as 95% of the stem cells have already died. Given that stem cell treatments cost $3,000 on average per treatment, PRP seems to be the better alternative for experimental nonsurgical treatment for canines. At this point in time, neither PRP nor stem cell treatment will guarantee that your dog will never require surgery. Long-term case studies will be required to understand the benefits of PRP and how long they can be expected to last.

Conservative Management – If you’re considering non-surgical options for your dog’s torn cruciate ligament, most likely you have a reason. It could be you cannot afford the very expensive surgery or you’re looking for a more conservative approach for an older dog. It may also be you are trying to learn as much as can about this condition and want to make the best decision for your pal.

The subject of surgery in torn cruciate ligaments seems to be a subject of controversy. One thing is for sure: when the ligament is torn, the knee is unstable and the bones are subject to an abnormal range of motion. This leads to a cascading effect, where the bones and the meniscus cartilage are subject to wear and tear which lead to degenerative changes. When the meniscus is affected, parts of it may need to be removed or repaired. Bone spurs, which develop in deteriorating joints, may start to form as early as 1 to 3 weeks after the rupture. A swelling just on the inside of the knee, known as a “medial buttress,” may be a sign that arthritis has set in, in cases where the tear is old. Surgery, appears to slows down degeneration, but it’s unfortunate that the degenerative changes cannot be reversed once started.

Non-surgical management consists of exercise restriction, anti-inflammatory medications, physical therapy and weight loss. These therapies can be effective in very small animals such as cats and dogs weighing less than 15 pounds, although these animals will develop some arthritis, they may regain almost normal function. Additionally, dogs that have ruptured the cruciate ligament on one side are more likely to tear the ligament in the other knee. So whether you are opting a surgical or non-surgical approach, rehabilitation is crucial.

The aim of rehabilitation is to restore knee range of motion and improve patellar stability by reinforcing the quadriceps.

Besides training the quadriceps muscle, stretching of the Hamstring muscle and articular retinaculum should be included in the rehabilitation program one month after trauma. Patient-education should be part of the therapy as well. The patient should receive home exercises which he/she should regularly do.

Whilst your dog already has existing CCL disease or luxating patella and is being managed conservatively, there is a risk of “flare ups” or exacerbation of clinical signs following trauma or inappropriate exercise. At this stage, the aims would be to control the inflammation and surrounding muscle spasm. It is also important to encourage careful limb use and prevent muscle atrophy. The soft tissues also need to be maintained. If your dog responds positively to the conservative rehabilitation programme the aims can be adjusted to include the above with greater limb loading, further limb strengthening and increased cardiovascular fitness. Restricted walking between prescribed exercise times is advised to ensure the knee isn’t overloaded alongside the specific controlled rehabilitation exercises.

| Timeline | Physiotherapy Aims | Rehabilitation Therapy options |

|---|---|---|

| Week 0 to 4 | Reduce inflammation |

|

| Reduce muscular guarding |

| |

| Improve core stability |

| |

| Increase strength |

| |

| Increase sensation and awareness of body position |

| |

| Maintain soft tissue length and flexibility |

| |

| Management at home |

| |

| Week 4 to 6 | Continue as above |

|

| ||

| ||

| Week 6 to 12 | Increase exercise tolerance |

|

| Continue to increase core stability |

| |

| Week 12 onwards | Return to full function |

|